How does Minnesota factor into the recent judgement against political genocide actions in Guatemala? The findings that have brought justice in the case relied on "The Minnesota Protocol."

Work on the protocol started in Minnesota 30 years ago by a team of lawyers concerned with growing international strife. They created a format for neutral scientific third parties to investigate claims of assassination and genocide after it was becoming apparent that in many offending countries, those investigations were being done by groups sympathetic to the leaders being accused of the crimes. The concepts were adopted by the United Nations in 1989 as a global standard to use to investigate such situations.

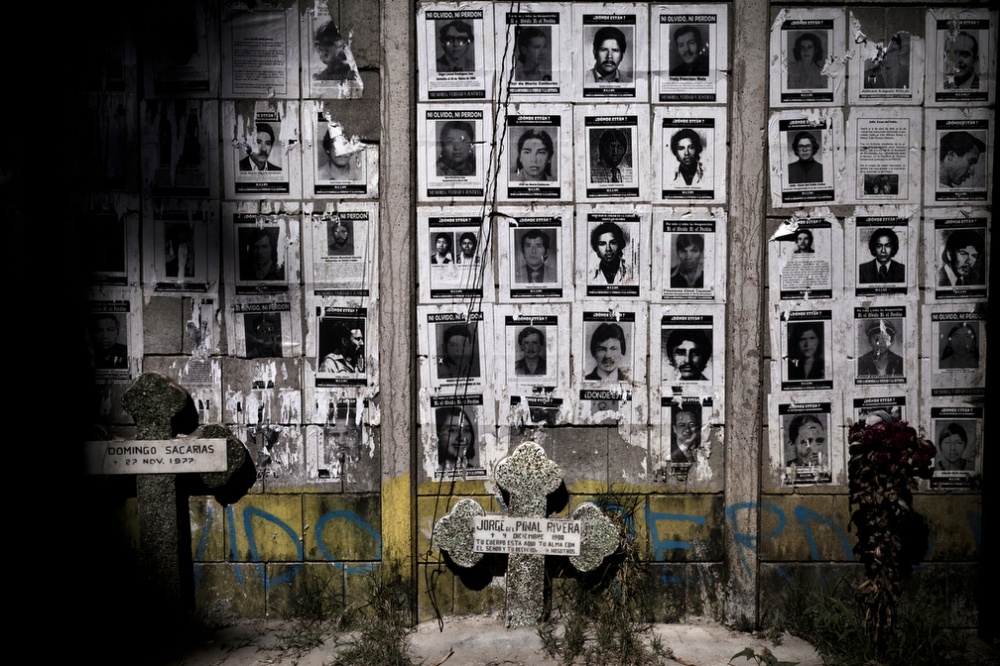

The testimony from scores of witnesses and survivors at the recent trial of former Guatemalan military dictator Efrain Rios Montt was no doubt gripping and emotionally gut-wrenching. Infants tossed into flaming homes. Pregnant women gutted, their fetuses cut from their bodies. Elderly men and women gunned down. Women and girls gang-raped inside churches. A former government soldier maintained his orders were to kill the Indians.

But the accounts did not prove on their own that what Amnesty International called a "government program of political murder" had taken place in the Mayan Ixil region and claimed the lives of at least 1,700 indigenous people during the 17 months after Montt seized power in a military coup in 1982.

Either they were exaggerating or lying, or the victims were the collateral damage and random casualties of a 36-year-long civil war that ended with a 1996 peace accord, the defense team posited.

But what helped seal Montt's fate this month as the first head of state to be convicted in his own country of genocide and crimes against humanity was the irrefutable evidence unearthed by a meticulous forensic investigation modeled after an internationally approved protocol devised in Minnesota in the 1980s.

In what was described as detached but riveting testimony that at times caused the courtroom to fall silent, forensic archaeologists and anthropologists from the Fundación de AntropologÃa Forense de Guatemala (Forensic Anthropology Foundation of Guatemala) presented evidence of clandestine and mass graves bearing the remains of victims of all ages shot in the head and thorax area, execution-style. Of the 50 bodies found beneath a soccer field, one-third of the victims were adults and the rest juveniles, one testified.

"Despite the shocking evidence, the Minnesota Protocol requires a neutral investigation in order to lend credibility to the ultimate prosecution," wrote courtroom spectator Ali Beydoun, director of the Human Rights Impact Litigation Clinic at the American University Washington College of Law.

"The Minnesota Protocol is part of our own protocol and the international standard for conducting these types of investigations," Fredy Peccerelli, the foundation's director, said Thursday, May 16, from Guatemala City. "Although we have improved and expanded on things over the years, we follow it as a minimum standard on a daily basis."

The protocol was the brainchild of the Minnesota Lawyers International Human Rights Committee, an advocacy group now known as the Minneapolis-based Advocates for Human Rights.

Formed in 1983 by Twin Cities lawyers Sam Heins, Tom Johnson, Donald Fraser and others, the group sought to undertake a major project with international implications. Heins sent a letter to David Weissbrodt, a University of Minnesota law professor then on sabbatical in London, and asked for his input. Weissbrodt wrote back about a lack of a uniform legal or medical standard in the way politically motivated assassinations were investigated throughout the globe. Often, he noted, entities in charge of launching the probes also were suspected of carrying out the slayings. What was needed: A uniform investigatory standard that was credible, neutral and beyond reproach.

The group endorsed the idea, researched the issue and consulted with local and international human rights, legal and forensic experts.

"We were seeking a protocol that closely modeled what a homicide police investigation entails -- the law, autopsies and forensics evidence," recalled Barbara Frey, an initial group member and now director of the Human Rights Program in the U's College of Liberal Arts.

Former Hennepin County medical examiner Garry Peterson and then-group volunteer Lindsey Thomas co-authored the autopsy part of the proposed guideline.

"Over the years, I have run into forensic pathologists in other countries who have used the protocol for death investigations, and the amazing thing to me is how well it has withstood the test of time," Thomas, now the county's assistant medical examiner, said this week.

Most of the protocol was hammered out at a conference in Spring Hill, Minn., in 1987. Attendees included forensic anthropologist Clyde Snow, a pioneer in mass-grave probes who helped train the Guatemalan foundation staff as well as others in Argentina and the former Yugoslavia.

The result was the "Manual on the Effective Prevention and Investigation of Extra-Legal, Arbitrary and Summary Executions."

Better known as the Minnesota Protocol, the guideline was adopted by the United Nations two years later. It has been used to conduct investigations and document genocide and human-rights abuses in places such as Rwanda and Bosnia.

Montt's historic conviction sheds more light on a country where an estimated 250,000 people were killed or disappeared during the civil war, said Kathryn Sikkink, a political science professor at the U.

"Although many people know more about the repression in Chile or Argentina, in terms of the absolute number of people killed or disappeared, as well as the relative number of victims in relation to the population, the scale in Guatemala was much greater than any place else in Latin America," said Sikkink, who wrote "The Justice Cascade," an award-winning book that documents the global impact of such probes in recent decades.

"It's good to know that the protocol still carries the Minnesota name," said Weissbrodt, now a Regents professor at the law school.

Although Peccerelli understands that Montt's conviction has set in motion appeals that could last years, he believes the legal maneuvering will not erase that justice was achieved.

"Our job was to present evidence of the crimes found on the remains and to translate what the victims told us through their bones," he said. "The physical evidence was not only powerful, but it helped corroborate the testimony."

Similar investigations using the Minnesota Protocol have led to genocide convictions in other corners of the globe such as Rwanda and Bosnia.

Saturday 18 May 2013

http://www.twincities.com/news/ci_23262230l

http://www.sciencebuzz.org/blog/minnesota-protocal-uncovers-global-human-atrocities

0 comments:

Post a Comment