The remains of two sailors who died more than 150 years ago when their Civil War-era ironclad ship, the USS Monitor, sank will be buried with full military honors Friday at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

The skeletons of the two Monitor crew members were recovered in 2002 from the ship, which went down in stormy seas in 1862 off Cape Hatteras, N.C. For more than a decade, military forensic scientists have been trying to identify the Union sailors and find living relatives, work that will continue after the remains are buried.

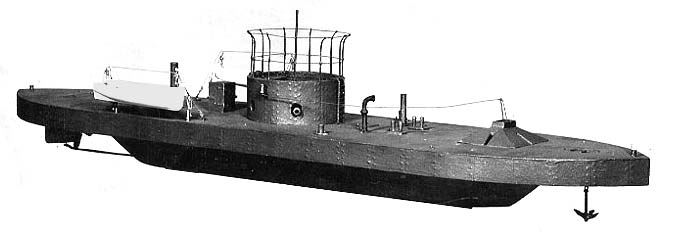

An 1862 photo shows members of the Monitor's crew sitting on deck.

"The nation makes a promise to bring them home and tell their families what happened to them," said David Alberg, superintendent of the Monitor National Marine Sanctuary in Newport News, Va. "That promise is still good 150 years later."

Launched in January 1862, the Monitor, with its 9-foot-tall rotating turret made from 8-inch-thick iron, boasted the latest shipbuilding technology.

At the Battle of Hampton Roads in March 1862, the Monitor squared off with its rival, the CSS Virginia, a Confederate ironclad built on the frame of an old Union ship, the USS Merrimack. It was the first battle between two ironclad ships.

The two exchanged fire over the Union blockade of Norfolk and Richmond. They fought to a draw and the blockade remained.

The remains are to be interred Friday at Arlington National Cemetery.

Later that year, the Monitor foundered on the open Atlantic in 17-foot waves, according to Mr. Alberg. It went down with a crew of 16 in an area off Cape Hatteras, an area known for rough seas.

"The Monitor is no more," wrote the ship's paymaster, William Keeler, who wasn't on the ship when it went down. "What the fire of the enemy failed to do, the elements have accomplished."

In the 1990s, divers from the Navy and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration began recovering portions of the ship, which sits in some 230 feet of water.

In 2002, divers uncovered two sets of human remains in the ship's turret, which had broken off during the sinking. The turret had filled up with sediment, marine life and coal from the ship's bunkers, creating what experts say was an ideal environment for preserving the sailors' bones.

"I distinctly remember looking inside," said Joseph Hoyt, 31, a NOAA underwater archaeologist who took part in the dive. "They were intact," he said of the bodies, "and laid out the way you'd imagine a skeleton."

Once the remains were uncovered, the Navy stopped the excavation and hauled up the 200-ton turret still filled with sediment.

The bodies of the 14 other missing sailors haven't been found and are thought to have been lost during the sinking or destroyed by natural processes.

The turret was trucked to the Mariners' Museum in Newport News, where archaeologists began conservation efforts, beginning with the bodies. "They were so well preserved, they were still wearing shoes," Mr. Hoyt said. "One of them had a wedding ring he was still wearing."

The bodies subsequently were sent to the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command at Hickam Air Force Base in Hawaii, where forensic specialists identify human remains from any American conflict. "There's no distinction whether this was someone killed in Afghanistan a month ago or someone killed in the Civil War," said Mr. Alberg.

Because the bones were so well preserved, the sailors' DNA could be extracted from the remaining tissue.

A number of people have come forward to take DNA tests in hopes of being identified as relatives of the sailors. No conclusive matches have been found although there are a few possibilities.

Andrew Bryan, a 52-year old elementary school principal in Holden, Maine, is one. He said his great, great uncle was William Bryan, a Scottish immigrant who sailed on the Monitor. While trying to find information about his ancestor on genealogy websites, he received a message from someone associated with the POW/MIA program.

"The Navy saw that I had made a post about three years ago," Mr. Bryan said. Although his DNA tests were inconclusive, the results were close enough that Mr. Bryan will be attending the ceremony Friday as a possible relative. "From the moment I knew it was going to happen, I had to be there," he said.

The bodies will be unidentified when they are interred in Arlington National Cemetery's Section 46. "The remains will have a group marker, the same as if there are group remains from a helicopter crash," said Jennifer Lynch, a spokeswoman for the cemetery.

Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus and the head of NOAA, Kathryn Sullivan, plan to attend the ceremony, during which the Army's Old Guard will transport the remains on caissons to the gravesite. Friday is the 151st anniversary of the Battle of Hampton Roads.

"In the middle of a conflict about the way our society would define itself, here you had a tiny little ship with a crew that was a snapshot of what modern America would become," said Mr. Alberg. "An integrated crew—with immigrants, Jews, escaped slaves—all serving on this ship floating in the middle of this conflict."

Friday 8 March 2013

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887323628804578346181040053980.html?mod=googlenews_wsj

0 comments:

Post a Comment